Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) 101

Explainers | Feb 12, 2026

This 101 explainer breaks down what the AMOC is, how it influences climate, what scientists are observing now, and what a changing AMOC could mean for people and ecosystems.

What Is the AMOC?

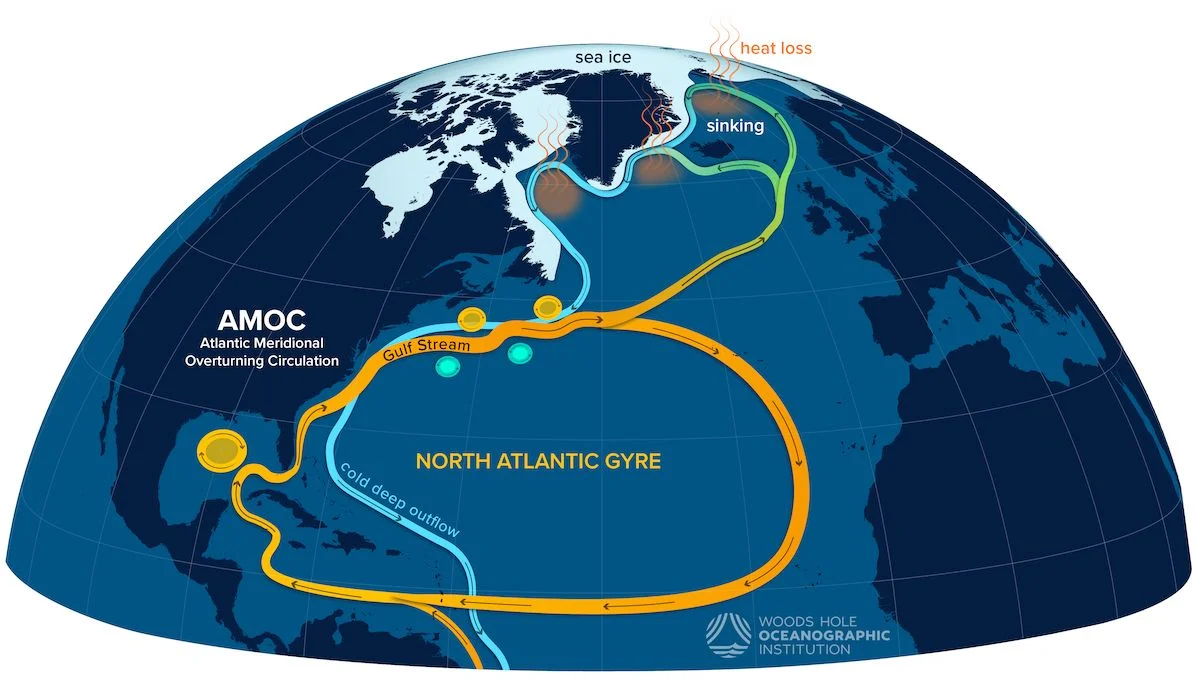

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation — often called the AMOC — is one of Earth’s major ocean circulation systems. Scientists sometimes describe it as a giant ocean “conveyor belt” that moves huge amounts of water, heat, salt, and nutrients around the world’s oceans. While the physics are complex, the idea behind AMOC is straightforward: oceans are not still. They transport heat and energy around the planet in ways that strongly shape climate and marine ecosystems.

It's basically a huge system of ocean currents in the Atlantic that moves warm, salty water northward near the surface and returns colder, denser water southward deep below.

- Warm, salty surface water flows northward from the tropics, in currents like the Gulf Stream, toward the North Atlantic.

- As this water moves north, it cools, becomes denser, and sinks in areas like the Labrador and Nordic Seas.

- That cold, dense water then travels southward at depth, back towards the tropics, completing a loop that helps drive global ocean circulation.

The AMOC acts like a planetary heat and water conveyor belt — a key link between the tropics and the poles. It carries tropical warmth northward and returns cold water back toward the tropics. This movement affects climate patterns, marine life, and even our weather.

Why the AMOC Matters for Climate and Communities

AMOC plays a key role in shaping Earth’s climate by moving heat, freshwater, and nutrients around the Atlantic Ocean. One of its most visible effects is on regional temperature: by transporting warm water northward, the AMOC helps keep parts of Europe and the North Atlantic milder than they would otherwise be. Many communities and industries depend on predictable climate and weather patterns, and disruptions to this system can have wide-ranging social and economic consequences.

Because the AMOC is closely linked to the atmosphere, changes in its strength can influence large-scale weather patterns, including rainfall belts and circulation systems that affect monsoons. Along coastlines, a weakening AMOC has been associated with higher relative sea levels, particularly along the U.S. East Coast. In the ocean, the AMOC also helps distribute heat, nutrients, oxygen, and carbon — factors that shape marine ecosystems and influence where fish and plankton species can thrive.

Even without a sudden or complete collapse, gradual changes in the AMOC can have meaningful impacts over time. Slower circulation can contribute to sea level rise, shifts in regional climates, and changes in marine ecosystems that fisheries and coastal communities depend on. Together, these effects highlight how the AMOC helps balance energy across the planet — and how changes to this circulation can ripple through climate, ecosystems, and human systems in ways that may not be immediately obvious, but are significant.

For communities that rely on healthy oceans and stable climate conditions, understanding these dynamics is essential. Preparing for a changing AMOC — through improved forecasting, adaptation planning, and resilient management — helps reduce risk and supports informed decision-making in a warming world.

AMOC is also one of the most talked-about parts of the global climate system. You may have seen headlines mentioning the system could collapse and bring dramatic climate changes. But the best available science says that a sudden collapse is not imminent, although the system is showing signs of gradual weakening.

Is the AMOC Weakening or Collapsing?

There are signs it’s weakening. Scientific records and model simulations suggest the AMOC is about 15% weaker than in the mid-20th century, likely due at least in part to increased freshwater input from melting Greenland ice.

However, the idea of an imminent, abrupt collapse is not supported by current scientific evidence. Most climate reports, including from the IPCC, conclude that the AMOC is more likely to continue weakening gradually over this century under continued emissions than to shut down suddenly.

Studies that do show collapse scenarios often do so using extreme, hypothetical conditions (for example unrealistically high freshwater input), rather than what’s likely in near-future projections.

How Scientists Study and Monitor AMOC

Because the AMOC operates across vast distances and depths, scientists rely on multiple tools to understand how it behaves and how it is changing. Long-term observational records track ocean temperature, salinity, and currents, helping researchers identify trends and variability. Climate models are used to explore how the AMOC may respond to future warming, freshwater input, and other changes in the climate system.

To understand what these large-scale changes mean for specific regions, scientists also use high-resolution regional models. These models allow researchers to translate global circulation patterns into place-based insights — including for areas like the Gulf of Maine and the Northeast U.S. Shelf.

At GMRI, our oceanography team uses advanced regional models coupled with biogeochemical data to examine how shifts in currents and temperature affect marine habitats, ecosystems, and fisheries in the Northwest Atlantic.

Can We Influence What Happens Next?

We can’t flip a switch to restore the AMOC. But there is a role for climate action: reducing greenhouse-gas emissions slows warming and melting in the Arctic and Greenland, which in turn reduces some of the pressures that weaken the AMOC.

Every ton of carbon avoided adds resilience to the climate system, helping keep changes to patterns like the AMOC more gradual and manageable.

Bottom Line

The AMOC is a critical component of Earth’s climate system. It’s an arterial system for the planet that delivers and transports heat, nutrients, and weather around the planet. While scientists see evidence it’s weakening, a sudden collapse is not currently supported by the best available research.

Instead, what’s most likely over the 21st century is gradual change with meaningful impacts on regional climates, sea levels, and marine ecosystems. Understanding this system helps communities and ecosystems prepare for, and adapt to, a changing ocean.