Intern Reflections: A Summer Studying Sea Level Rise

Perspectives | May 9, 2023

by Connor Brooks

Coastal Hazards Research Technician

Former GMRI Climate Center REU intern and University of Wisconsin-Madison Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences undergraduate Connor Brooks shares his experience studying sea level rise and Union Wharf in summer 2022. Connor has since joined GMRI as a Coastal Hazards Research Technician.

Within three weeks of arriving in Portland last summer to intern with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s Climate Center, I saw evidence of sea level rise first-hand. It was late one night in mid-June, and the full moon brought with it a higher-than-average high tide that flooded several wharves along Commercial Street.

I took my shoes off to wade down Portland Pier, where I watched a late-night delivery truck turn around to avoid driving through a foot of ocean water.

As I made my way westward along the waterfront, I noticed water creeping into a parking lot, breaching the rims of a parked car. In other low-lying areas of the city, water pooled near storm drains that, if only for a brief time, were now below sea level.

There’s a certain eeriness on a still, cloud-free night like this. Late in the evening, while most are asleep, the water slowly crawls into the city. Quietly bubbling up through low-lying storm drains or spilling over the waterfront’s edge, the water wanders up the street and around a corner as if it came to simply check the place out. It might knock on a few doors, but it won’t yet come inside. Soon enough the tide will go out and the water will silently drain back to the sea. Come back in the morning though, and you’ll notice the water has left a crisp line of seaweed at its maximal extent as if to say, “I was here” (along with returning a bit of our garbage to us).

I would go on to witness these 12-foot tides seven more times during my summer in Maine. While Portland is no stranger to the occasional extreme tide, they’re starting to come more often and creep ever higher due to sea level rise, putting much of the city’s waterfront at risk of repeated flooding and saltwater intrusion if adequate adaptation measures are not implemented.

I spent my summer in Portland on a National Science Foundation-funded research internship with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s Climate Center. My research project sought to understand the combined impacts of sea level rise, high tides, and storm surge on Union Wharf structures and operations over the next decade. Union Wharf is a key pillar of Portland’s working waterfront and was recently purchased by GMRI. As the new stewards of Union Wharf, GMRI has an opportunity to develop and implement sea level adaptation strategies that will equip Portland’s working waterfront to thrive far into the future.

Union Wharf is well-prepared to withstand occasional ocean flooding. The nature of fishing and other marine industries necessitates many of the buildings being salt-water resistant on the ground floor where lobster tanks and bait buckets occasionally slosh around. However, as tidal conditions change and higher floods expose new risks, sea level rise adaptation will become a necessary part of the wharf’s planning strategy. My project was to be a critical first step in developing a comprehensive climate resilience plan for Union Wharf — and, hopefully, provide a roadmap for the Climate Center and partner organizations to usher in an era of climate-smart working waterfronts throughout the region.

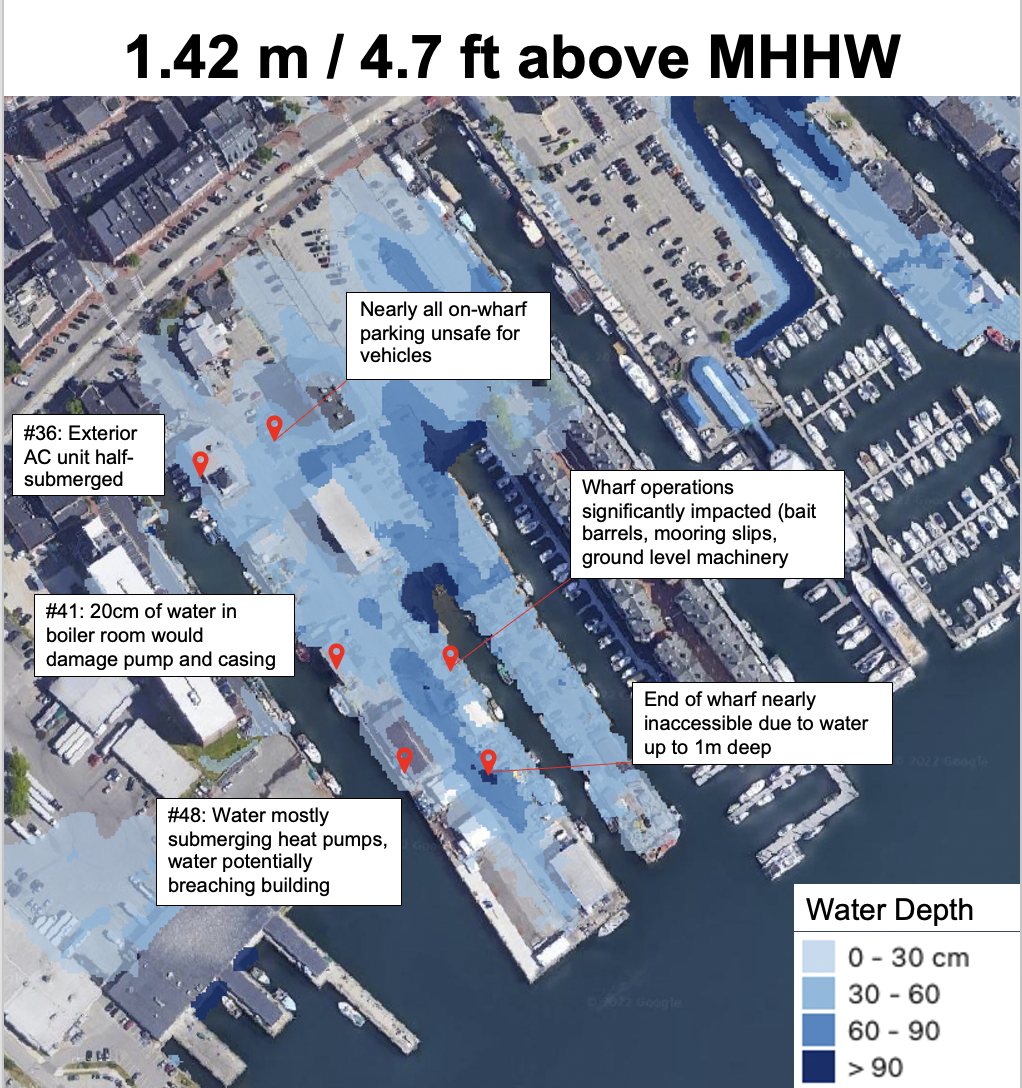

An initial step in building a climate resilience plan for the wharf was to conduct a sea level risk assessment — that is, how will higher sea levels affect the wharf? Through several site visits and discussions with Tim Reich, GMRI’s facilities manager, we determined the primary concern was exposure of certain key utilities such as heat pumps and boilers to water damage. If a boiler pump or casing were to be flooded, an unheated building and frozen pipes could bring some wharf operations to a standstill and result in costly repairs. Fortunately, many of these utilities are slated for more energy-efficient replacements or are capable of being elevated at relatively low-cost.

The next step was to determine the likelihood that these utilities would flood over a 10-year planning horizon, a period during which several of the utilities of note would be up for standard replacement (and subsequent repositioning). First, I determined the elevations of these utilities using hand measurements and highly accurate, publicly available elevation data measured by lasers mounted to aircraft (called LiDAR). Next, I combined the latest local sea level rise projections from the 2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report, written by a group of U.S. government agencies, with future tide predictions at the Portland NOAA tide gauge, storm flooding statistics, and year-to-year sea level variability to get estimates of the highest annual astronomical tide, the 10% annual chance flood level, and the 1% annual chance flood level (often referred to as the 10 and 100-year flood levels). I then combined the local flooding predictions for the next decade with the utility elevations to produce several flooding impacts maps, such as the one below of what a 10% annual chance flood could look like at the end of the decade.

These results will now be used to inform adaptation strategies that may include repositioning key utilities to the second floor or roof or replacing older units with more resilient systems. This early impact assessment will give Union Wharf decision makers time to identify customized adaptation solutions and act on a manageable timeline.

The high tides I witnessed this summer weren’t high enough to have any harmful impacts on the wharf, but sea levels are rising, and, over the coming decades, higher tides will bring with them heightened flooding risks. The relatively slow march of sea level rise means we still have time to implement smart, forward thinking coastal adaptation strategies that will protect working waterfronts throughout the Gulf of Maine to ensure these vibrant coastal economies continue to thrive for generations to come.

Read More

-

![Maine scientists use new tools to help improve flood preparedness]()

Maine scientists use new tools to help improve flood preparedness

Press Clips

-

![With sea levels rising, Maine group seeks tide watchers]()

With sea levels rising, Maine group seeks tide watchers

Press Clips

-

![Maine climate scientists warn of more frequent king tide flooding without storms]()

Maine climate scientists warn of more frequent king tide flooding without storms

Press Clips

-

![Maine Islands Plan for Climate Change]()

Maine Islands Plan for Climate Change

In December 2022, students, teachers, and community members from North Haven and Vinalhaven took part in a community resilience training workshop developed by our Municipal …

Perspectives